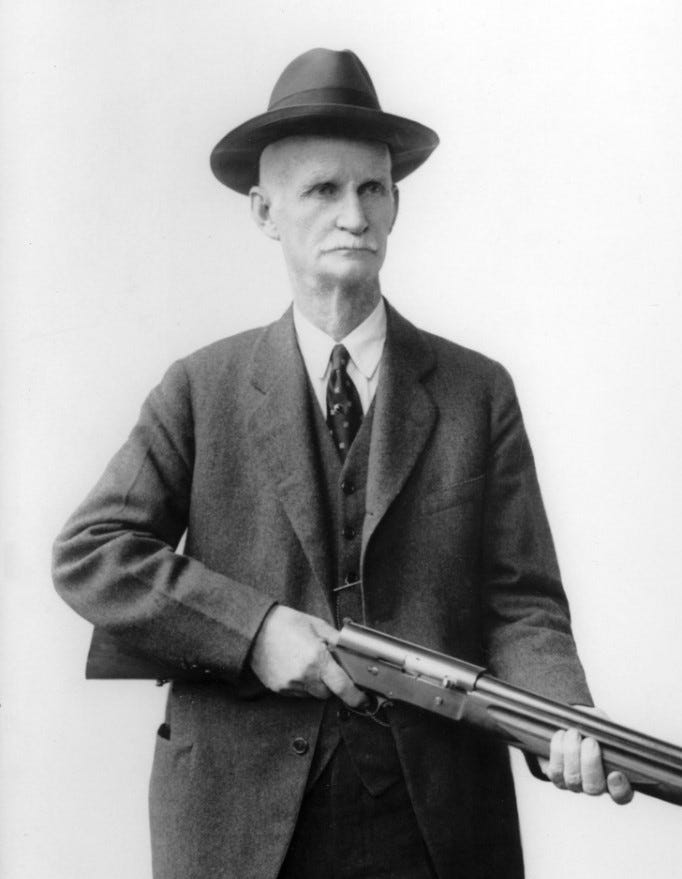

John Moses Browning was among the most prolific of gun designers, and his designs had a big impact. A multitude of sporting rifles and shotguns, the 1911 pistol and its whole family of semi-automatic pistols, the Browning Automatic Rifle that served so famously in both World Wars, and last but certainly not least, a family of belt fed heavy machine guns that still sees use more than a century later, Browning had an outsized influence on weapons design through the 20th century. But he was only one among many attempting to design a working, practical fully-automatic machine gun in the late 19th century.

Hand Cranked Machine Guns

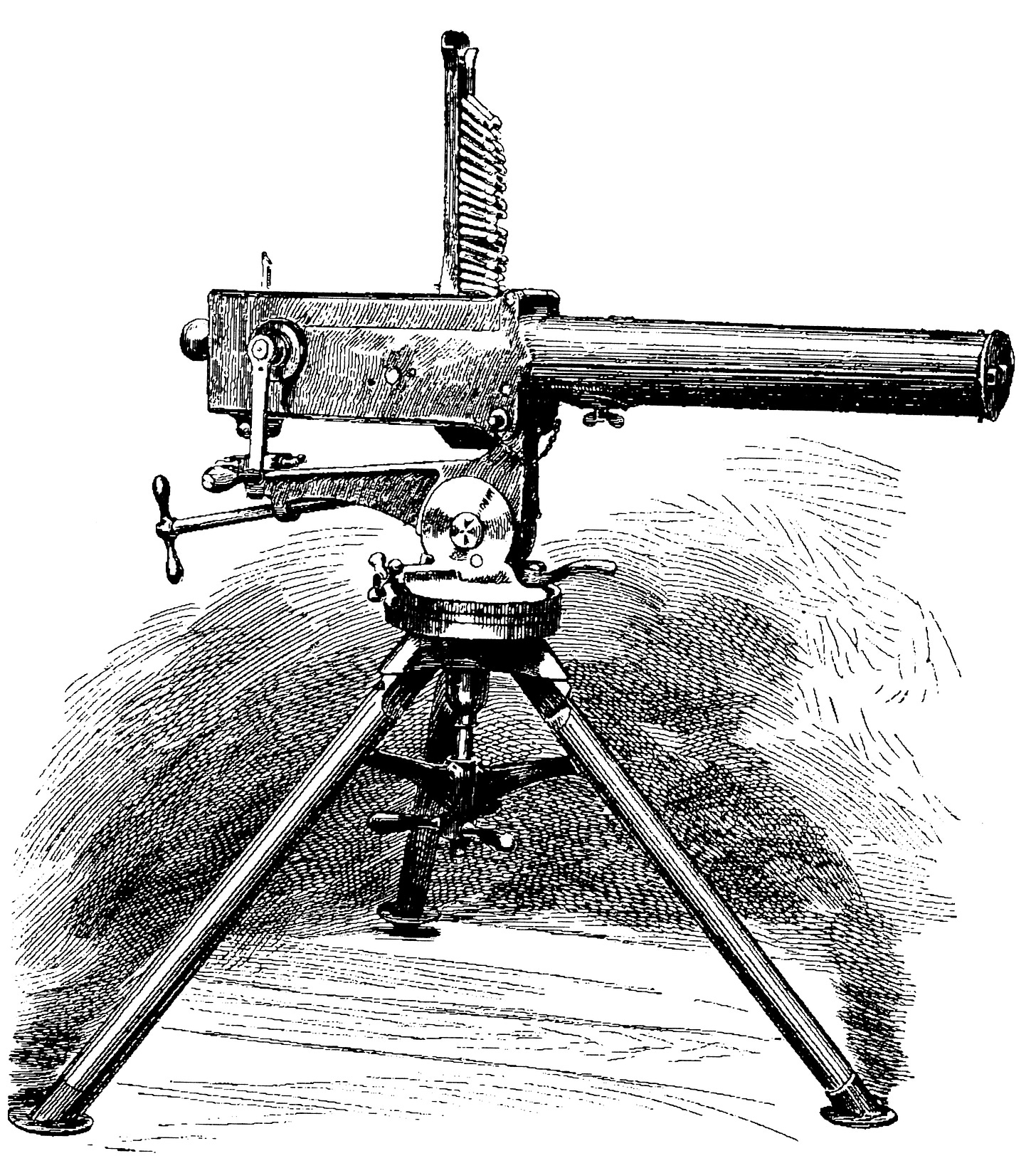

The first practical machine gun to enter use was the Gatling Gun, designed in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling, which saw some use in the US Civil War, as well as colonial and frontier conflicts through the turn of the century. It used multiple barrels revolving around a central axis, with a mechanical loading, firing, and unloading system to feed cartridges from a hopper into each barrel in turn. A contemporary design, the Agar machine gun, used a similar hand-cranked feed system but with a single barrel. These guns were big and heavy, mounted on cannon-type carriages, and not very mobile. The theory of machine gunnery had not been developed yet, so these weapons were looked at as a species of artillery, generally a replacement for grapeshot or cannister. Still, with a high chance of mechanical failure in the field, these early machine guns were not highly trusted by the soldiers, and acceptance was slow.

Later, by the time of the Spanish-American war, somewhat smaller models of hand-cranked machine guns came into use, including the use of tripod mounts instead of cannon carriages. The increased portability allowed the weapons to be deployed for infantry support, instead of placed with the artillery. This allowed for the evolution of modern machine gun tactics, which saw further development during the First World War.

After the Civil War more manual machine guns were developed all over the world, from the French Reffye mitrailleuse to the British Gardner and Nordenfeldt guns, they saw use but also failures, and they needed the handle continuously cranked (or in the case of the Nordenfeldt gun, the lever constantly worked), for the gun to continue firing. Many inventors saw the design of a true automatic machine gun as a lucrative goal.

The First Automatic Machine Guns

The three big names in the early development of true automatic weapons are Benjamin Hotchkiss, Hiram Maxim, and John Browning; all American inventors serving a primarily European market.

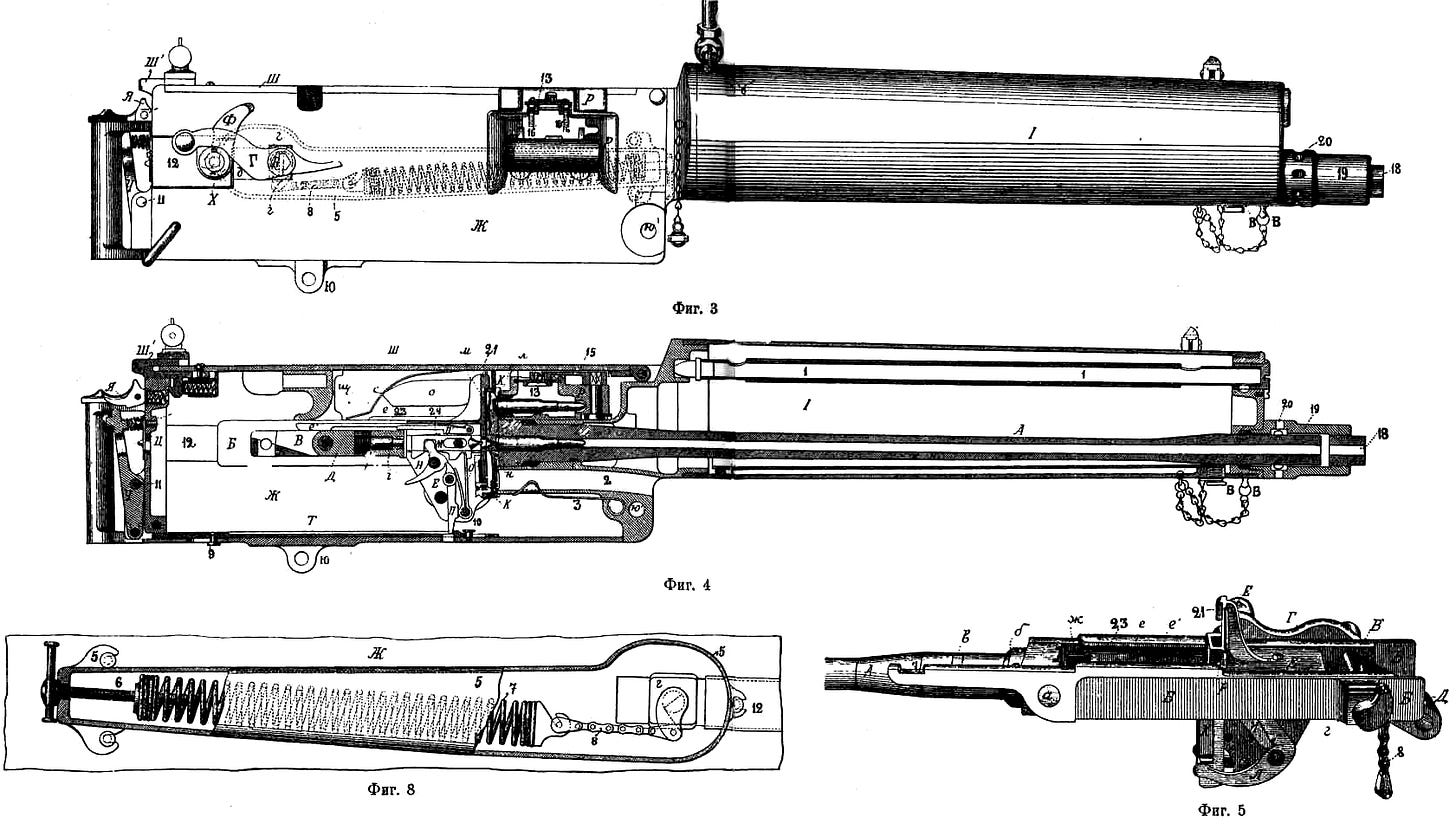

The first to succeed at the goal of a fully automatic machine gun was Hiram Maxim, who developed and brought his gun to market in 1885. The Maxim gun revolutionized warfare in the colonial period, and again during World War I. Early Maxim guns were hopper fed, like the Gatling gun, and used black powder (primarily 577/450 Martini-Henry, in British service), but used the recoil of the fired cartridge to extract, eject, and reload the gun, allowing for continuous fire without manual operation. Black powder Maxims were subject to rapid fouling, and generated plumes of smoke obscuring vision, making them unpopular like the earlier hand cranked guns, but soon smokeless cartridges, along with belt feeding, came into use and new models of the Maxim lead to the infamous couplet about colonial warfare:

Whatever happens, we have got

The Maxim gun, and they have not.

Maxim guns were produced in many smokeless calibers, including 8mm Mauser, 7.62x54mm Russian, .30-06 Springfield, and.303 British. Copies and derivatives including the MG08, Vickers, and PM1910 saw heavy use all over the world through the 1950’s.

Benjamin Hotchkiss developed a revolving barrel cannon, similar to an oversized Gatling Gun in the 1870’s, but more important was the firm he established in France, which produced the model 1897 automatic machine gun. The Hotchkiss machine gun was an air-cooled weapon, with large cooling fins on the barrel, and was gas operated like modern automatic rifles. Instead of a belt or a hopper, it used rigid feed strips, typically holding 80’s rounds of ammunition. Like the Maxim, this was a commercially produced weapon sold to many countries, and so made in many calibers. The Hotchkiss was adopted by the French army in several variants, and the US Army as the M1909 Benet-Mercie machine gun. In addition, Imperial Japan based most of their heavy and even light machine guns on the Hotchkiss design.

John Browning began working on a machine gun design in 1889, but it wasn’t until 1892 that he had a patentable design, which became the Model 1895 Automatic Machine Gun, with was then sold to Colt for production and marketing. This was another commercial design, and was produced in several calibers, but most notably in .30-40 Krag, 6mm Lee Navy, and .30-06 Springfield. The 1895 is air cooled, and gas operated, but due to its swinging operating lever under the barrel, it came to be known as the “potato digger”. It saw service with volunteer units in the Spanish-American war, notably with the Rough Riders, and was sold around the world. Due to the design being air cooled, the gun had heat issues which could cause it to seize up during sustained fire. As a result, by World War I it was largely relegated to a training weapon for US military purposes, or used by National Guard units domestically. Later, the design was sold to Marlin, who produced an improved model, the 1917, which fixed some of the issues and saw service as an aircraft and tank machine gun during the interwar period. Still, it remains an interesting footnote to the much more successful machine guns Browning later developed.

Browning’s Guns

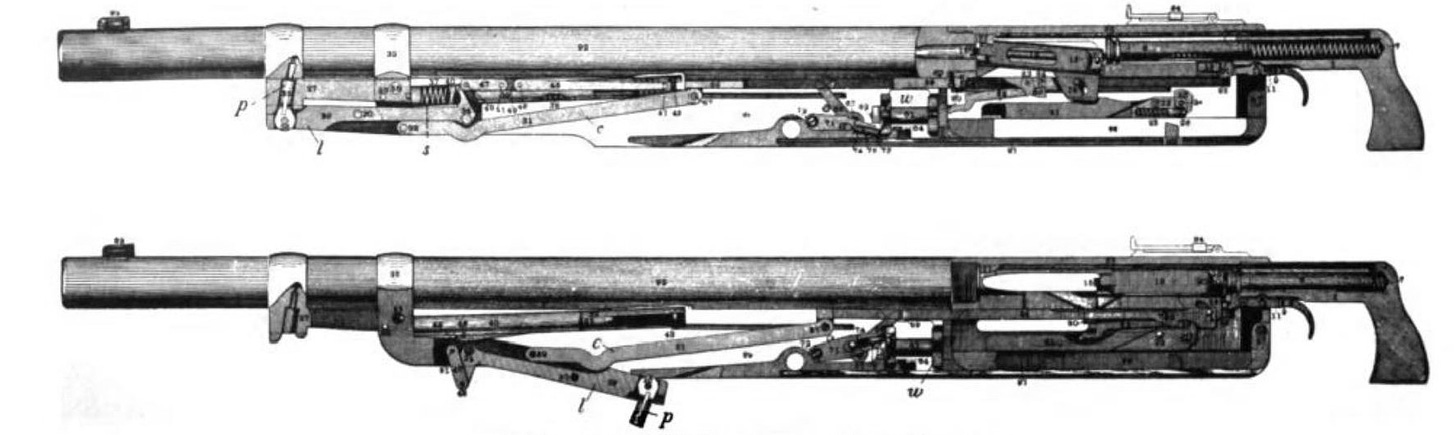

In response to the demands of World War I, as well as to correct some of the deficiencies of the model 1895, Browning designed a recoil operated, water cooled, belt fed machine gun. While externally similar to the Maxim, Browning’s design had the same pistol grip as the model 1895 instead of the spade grips and butterfly trigger of the Maxim. More importantly, the Browning water cooled gun, the M1917, has a vastly simpler internal design than the Maxim, with a bolt and firing pin assembly more akin to modern assault rifles. The 1917 turned out to be rugged, reliable, and an overall excellent design. They saw some use at the end of World War I, and then were produced commercially by Colt for sale all over the world, particularly in South America and Poland. In World War II and Korea they were still in common use by the US Army, and were also provided lend-lease to the UK and others.

In addition to the 1917, Browning saw the need for a light machine gun by US forces in France, and the French 1915 Chauchat was not up to standard. For this role, particularly “walking fire” in support of infantry advances, Browning designed an automatic rifle, the famed BAR. The BAR is essentially a large, heavy .30-06 rifle firing fully automatic using a gas operated mechanism, loading from 20 round detachable box magazines. As an automatic rifle, as opposed to a true light machine gun, the barrel was not easily changeable, limiting its use for sustained fire, but still the BAR remains well loved. After the war, the BAR was produced commercially as the Colt Monitor. Intended for civilian sale, the Monitor was prohibitively expensive ($3000 in the 1920’s), limiting its interest to government sales, with some stolen by gangsters (famously Clyde Barrow). Variants were also produced by FN Herstal during the interwar period, and were used by several nations including Poland and Belgium. The BAR remained in US service through Korea, being retired in the min 1950’s, prior to the adoption of the M60 general purpose machine gun.

After World War I, Browning and the US military saw the need for a weapon similar to the 1917, but more portable. To accomplish this, Browning created the M1919 air cooled machine gun. The 1919 was considered a light machine gun by the army, but by most standards would be a heavy machine gun, as it was belt fed, tripod mounted, and crew served. In fact, the 1919 is almost exactly the same as the 1917, and shares surprising amounts of parts interchangeability. The 1919 has a heavy barrel with a perforated barrel shroud to manage heat, and as a result the sights are positioned a little differently than on the 1917, but otherwise the receiver, bolt, and operating mechanism is largely the same. The 1919, in addition to being highly successful as an infantry support weapon, saw widespread use in variations as an aircraft machine gun and as a tanker machine gun.

The big brother in many ways to the 1917 and the 1919 is the M2 .50 caliber machine gun. This legendary weapon is essentially a scaled up 1919 in .50 BMG. It has been in service since the early 1920’s and is still in use today, in tank, aircraft, naval, and fixed emplacement roles. The M2, as a heavy support weapons, is a little too big to be readily moved, although a crew can disassemble and move one quickly enough when called for.

M1919 In Depth

The Air cooled, belt fed M1919 was produced in several versions, but the most common for ground use were the M1919A4 and M1919A6. The A4 was tripod mounted, functioning as a middle ground between the M1917 and the BAR; essentially a crew portable heavy machine gun that could be moved up with the riflemen. The A6 was an attempt to reconfigure the weapon into a general purpose machine gun like the MG34, by replacing the booster with a conical flash suppressor and adding clamped on bipod, carry handle, and buttstock.

Originally, the 1919 used the same cloth belts as the 1895/14 and 1917, as it was chambered in the same .30-06 cartridge. These belts could be reused with the help of a belt loader, as well as being used for other purpose like jury rigging a sling or wrapping the barrel shroud to provide additional protection for the hand against heat. In fact, by wrapping the barrel and tying on an ersatz sling, the 1919 was sometimes used as a squad automatic weapon in the Pacific campaigns. Later, disintegrating steel links were introduced as well. After the founding of the state of Israel, many surplus 1919’s were sold to the IDF, who adapted the weapon to .308 and designed a new link that could accommodate .308. .30-06, and 8mm Mauser.

The M1919 was the standard US tank machine gun in World War II, and a variant was widely used in aircraft including the B17 until it was deemed underpowered (at 30 caliber) for aircraft use and replaced with variants of the M2. In the M4 Sherman tank there were 3 M1919’s in ball mounts and pintle mounts, as driver gun, coaxial machine gun, and commander gun (pintle mounted by the turret hatch.