Browning Machine Guns: The 1919a4

It's Theory and Mechanism

Today we will be taking a closer look at Browning machine guns, using the M1919 as our point of reference. The M1917 and M1919 are virtually the same gun, only differing in the barrel, cooling mechanism, and the sight positions, while the M2 50 caliber is very similar but scaled up.

Last time we explored the history and development of machine guns up to World War I and immediately post-war Browning designs. Today we’re going to get into the mechanism and use of these types of guns.

The example gun that I’m working with is an M1919a4 which was sold to Israel probably in the 1950’s, where it was converted to 308. While the original caliber for the M1919 was 30-06 Springfield, the guns were converted to many other calibers, particularly 8mm Mauser and 7.62 NATO/308. This gun came back to the US as a parts kit and was then rebuilt as semi-auto.

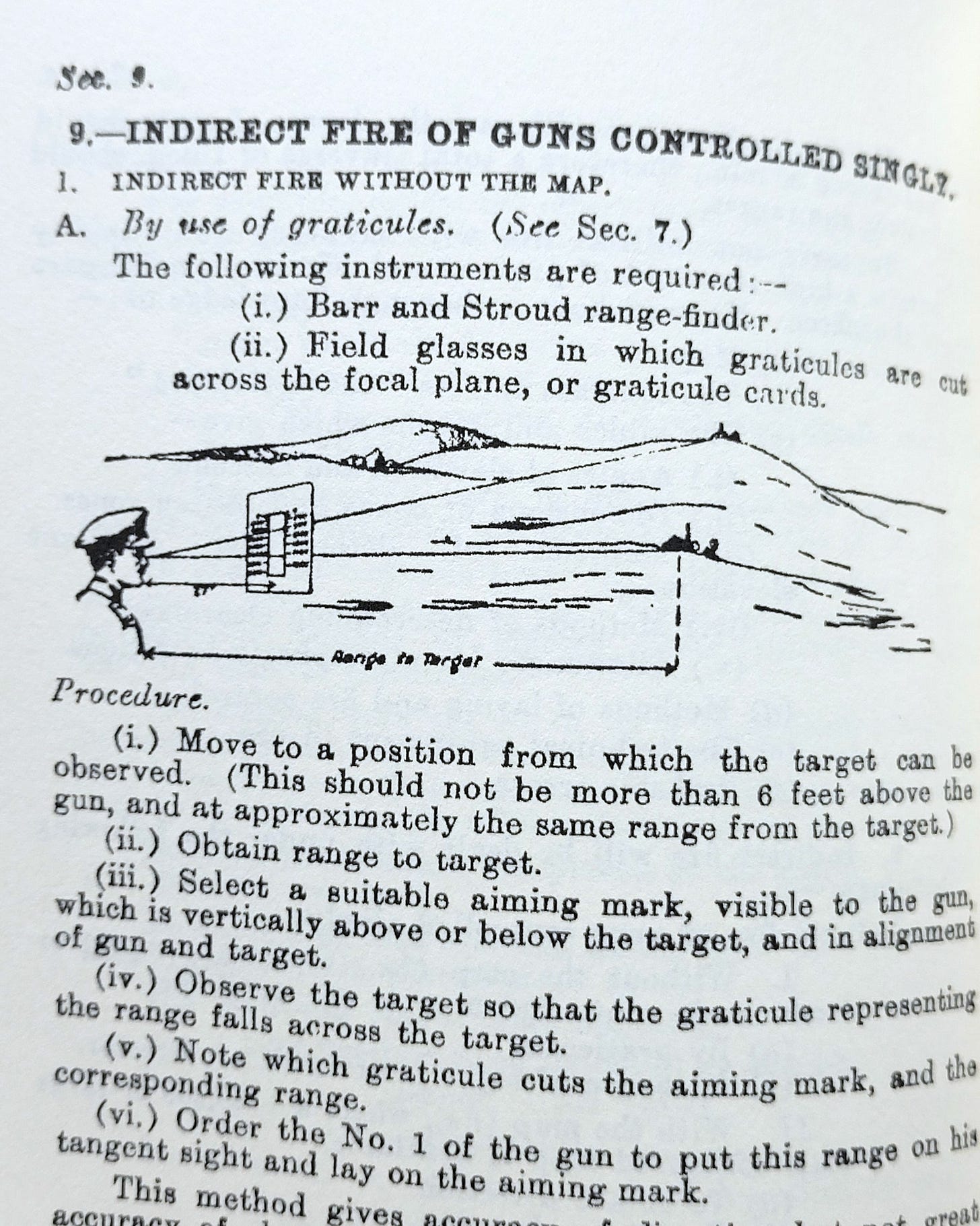

One of the big differences with machine guns versus conventional rifles is the use of indirect fire; like artillery, machine guns can be deployed to engage targets that the gunners cannot see. Using the traversal and elevation tool, which helps to connect the gun to the tripod, the relative position of the barrel, and thus the point of aim, can be set. Machine guns are not accurate weapons in the conventional sense, but are area saturation weapons. The area targeted by the machine gun is called the beaten zone, and forms an extended oval; the dimensions of the beaten zone are adjustable by altering the elevation, but anywhere within the targeted area will be in danger of being struck by bullets. The techniques of indirect fire with machine guns were developed during World War I, when the British termed it Barrage fire. The British would use entire batteries of Vickers guns for barrage fire against German positions, forcing enemy soldiers to keep under cover to avoid the deadly rain.

To use indirect fire from a map, the gunners need to have prepared a grid map of the battlefield, and position the gun with known zeroes for points of reference when aiming. In addition, the gun team will need to have communication with forward observers who can update them on enemy positions, with reference to the established grid squares. Then, the gunner can set the traversal and elevation on the gun to aim for the correct positions. As conditions on the battlefield change, the aim can be adjusted.

Indirect fire can also be used, in a more impromptu manner, when there is a known target obscured by hard cover like a hill slope. The gunners need to calculate the necessary trajectory to “drop” the bullets onto the target, and then aim at the intervening obstacle, raining fire in an arc onto the hidden target.

All types of indirect fire need to be used cautiously, particularly as friendly forces could be located between the machine gun emplacement and the target, and bullets will be flying over their heads. These, along with most other techniques of modern warfare, require organization and solid chain of command, where command knows where their assets are located and where the enemy is.

A good introduction to techniques for indirect fire can be found in The Employment of Machine Guns from The Naval & Military Press. The book is a collection of British military training manuals on machine gunnery from the end of World War I. While the book is dated in some regards, the underlying information hasn’t changed much in the use of heavy machine guns, although today you likely wouldn’t need to solve trigonometric equations by hand when calculating trajectories to aim the gun.

The belts for the 1919 can be either cloth or disintegrating links. The cloth belts are the same ones used with the M1917, and would also work with the 1895. The metal links were introduced for aircraft use in the 1930’s, but never fully replaced the cloth belts during the gun’s service life. Today, cloth belts are easier to get but harder to use, so links are preferred.

When loading the gun, the top cover can be opened and the belt placed in the action. Then, the cover closed locking the belt in with the feed pawl. Alternatively, cloth belts have metal tabs that can be inserted through the belt feed slide, locking into the correct position. With disintegrating metal links, starter tabs can be used to serve the same purpose. This allows for quicker loading without opening the top cover.

Work the charging handle to strip out the first cartridge and load it into the breech. The cartridge is pulled back from the belt, dropped down below the line of the belt, and then inserted into the chamber. The action of moving the bolt back and forward causes a cam to actuate the feed pawl, moving the belt along so the next cartridge is in position. Cloth belts will continue to the right when emptied, while links and spent casings will be discarded below the gun.

The M1919 is a closed-bolt design, meaning that the gun uses a firing pin/striker in the bolt which fires the gun when the bolt is closed and locked. As a recoil operated gun, the entire barrel moves back in battery when it fires. Because they fire from the closed bolt, heat is a particular issue with Browning machine guns. Excessive heat in the barrel can cause a cook off, when ambient heat from the barrel causes the powder in the chambered round to ignite, firing the gun without pulling the trigger, potentially even causing run-away full auto fire.

While the M1917 used a water jacket as a heat sink to dissipate the heat, the 1919 is meant to be more mobile, and so the water jacket was done away with. Instead, it uses a heavy barrel which can absorb more heat in the first place. Supplementing that, the barrel is covered by a perforated barrel shroud to move air over the barrel and assist cooling, as well as help keep the gunners hands off the hot barrel and prevent burns.

To assist the recoil operation of the gun, at the end of the barrel jacket there is a large booster, basically a cup that catches releasing gasses uses them to push the barrel back. The M1919a6 variant replaces the booster with a large conical flash hider to assist with the same thing.